PART 2: AI Defence, Persistent Conflict, and Complex Systems Warfare

Persistent Competition and the End of the Peace–War Dichotomy

This series explores how frontier AI and sub-threshold statecraft are dissolving the old peace–war divide, and sets out key concepts defending open societies amid complex-systems warfare.

Part 1: War is Not How Wars are Waged

Part 2: Persistent Competition and the End of the Peace–War Dichotomy

Part 4: Frontier AI, Control Dilemmas, and the Race for Supremacy

Part 5: Offensive AI, New Weapons, and New Risks in Escalation

Part 6: Defensive AI, Resilient Infrastructure, and Safeguarding Society

Part 7: Conclusion (Navigating an Unseen Battlefield)

Part 8: Appendix — The Human-AI Relationship

It is crucial to understand today’s active, adversarial security environment before we can craft an effective AI-defence strategy.

War and Peace

Classically, international law and political theory treated war as a binary condition: two states are either at peace or at war, with war marked by declared armed conflict and violence.

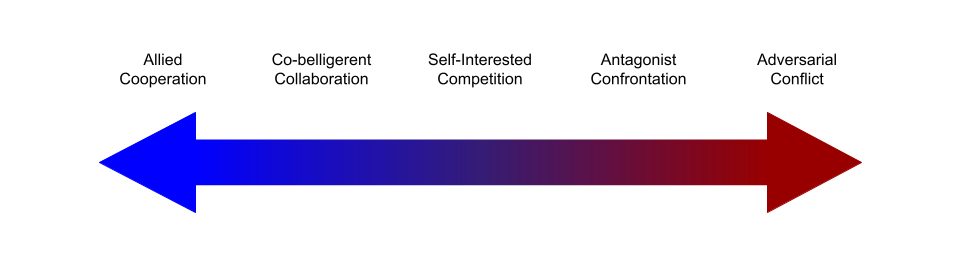

In reality, however, the geopolitical environment is better described as a continuum of competition that never really switches off. Great powers and many smaller actors are constantly jockeying for position, employing coercive and subversive tactics that stop short of open warfare. The U.S. Department of Defense formally embraced this view in its “Competition Continuum” doctrine,1 which describes “a world of enduring competition conducted through a mixture of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict.”

In other words, instead of an on/off switch between peace and war, we have a spectrum ranging from cooperation at one end, through intense rivalry and non-kinetic conflict, all the way to occasional outbreaks of direct fighting. States can be economic partners in one domain while sparring in another, and adversaries may engage in constant cyber- and information-operations even if their militaries aren’t engaged in conflict. Importantly, this means that the strategic objectives of two nation’s may be such that they can each walk away as ‘victors’ from an intense competition, both narratively and literally. Total conquest is an exceedingly rare objective, usually born of extreme ideological commitments.

Grey Zones

Why has this persistent competition become the norm? One reason is that the grey-zone tactics mentioned earlier are simply more cost-effective and less risky than traditional military aggression. Hostile cyber-operations, information campaigns, economic pressures, and proxy conflicts can undermine an adversary over time without triggering the kind of international response or domestic backlash that an outright invasion would provoke. These sub-threshold methods offer deniability and flexibility. A state can calibrate pressure on a rival – disrupting supply chains here, spreading a disruptive rumours there – to probe weaknesses or gain leverage, all while maintaining peace and plausible deniability. If the target doesn’t respond, then gains accrue; if the target does push back, the aggressor may be able to deny involvement or dial down the activity to avoid escalation.2

In risk-adjusted terms, the payoff of such operations is often superior to open warfare. Military action carries huge risks: you will lose lives, risk inviting harsh sanctions or coalition retaliation, or even spark a considerably larger war. But well-timed sabotage, sanctions, or disinformation campaigns can achieve a strategic effect (say, delaying an adversary’s weapons programme or swaying an election outcome) with minimal immediate consequences. Although kinetic force is stilled used today, most often in targeted strikes, it is usually held in reserve as a deterrent. The primary contest is a series of ongoing contests, where citizens, economies, and networks become the battleground.

Competition Continua in Greater Depth

Within the continuum of AI governance and competition, sovereign nation states exhibit a range of behaviours that reflect their political, economic, and security priorities.

Allied cooperation: At one end of the spectrum, states with closely aligned interests, values, and security concerns may form robust alliances for AI research, regulation, and capacity-building. These alliances encourage the free flow of data, harmonised standards, and the joint development of foundational models to prevent duplication of effort. By pooling resources and integrating supply chains, allies can accelerate innovation and reduce their vulnerabilities, while establishing a common regulatory framework that fosters trust and cooperation.

Co-belligerent collaboration: Slightly further along the continuum, countries that do not necessarily share a deep ideological alignment but have overlapping interests, such as responding to a shared security threat or achieving specific commercial goals, may engage in more limited collaborations. Here, expediency takes precedence over long-term geopolitical aspirations. For instance, two countries might coordinate on AI-driven cyber defence to mitigate an immediate threat or enforce a red-line, without extending that cooperation to broader AI applications or regulatory harmonisation. Although this approach can be mutually beneficial, cooperation remains contingent on existing incentives and dissipates if strategic interests diverge.

Self-interested competition: Many states will occupy a middle ground, focusing primarily on preserving or enhancing their own strategic advantage. In self-interested competition, states selectively engage in partnerships when it bolsters their domestic AI ecosystem or furthers national interests, while still maintaining guarded relationships with potential rivals. These countries may participate in multilateral forums for establishing baseline standards or norms but will resist any constraints they perceive as undermining their geopolitical competitiveness. This posture can lead to incremental progress on issues like AI ethics and safety, in a narrow sense, but is inherently fragile, as each participant remains wary of ceding strategic ground.

Antagonist confrontation: If competition intensifies (or if dynamics feature adversarial polarity), some states may shift towards antagonist confrontation, wherein rivalry extends beyond healthy competition into active attempts to undermine each other’s technological and regulatory progress. This might involve cyber espionage, targeted disinformation campaigns, or the strategic disruption of supply chains to curtail a rival’s AI developments. While not rising to the level of direct military conflict or the application of economic statecraft, these hostile tactics aim to degrade an opponent’s AI capabilities and erode public trust in their systems. The risk of escalation becomes acute here, as retaliatory measures can easily spiral into broader conflict in a tat-for-tat manner.

Adversarial conflict: At the extreme end of the spectrum lies adversarial conflict, characterised by open and active hostilities in which economic, military, and AI-enabled capabilities are weaponised to enforce a worldview, with mandatory physical compliance. States in this position may deploy advanced autonomous systems in warfare, engage in large-scale cyber-offensives, or sabotage crucial AI infrastructure to gain battlefield or strategic advantage. In such scenarios, multilateral governance frameworks and ethical agreements collapse under the weight of perceived existential threats. The consequences can be catastrophic, not only for the combatants but also for global AI governance efforts that might be permanently fractured by entrenched animosities.

Alignment dynamics of national and multinational corporations

Although sovereign states remain primary actors, national and multinational corporations (MNCs) increasingly wield significant influence over AI research and deployment, particularly for Hyperscalers, fabs, and foundries. Their alignment with governments is at least somewhat fluid, reflecting a shifting matrix of economic incentives, regulatory pressure, and reputational concerns.

Corporate ‘co-belligerence’ and self-interest: In many instances, corporations and governments act as co-belligerents on specific AI initiatives, driven by temporarily aligned commercial and security interests. Companies seeking access to lucrative public-sector contracts or favourable regulatory regimes may closely align with government objectives, including technology transfer or standard-setting. Yet, corporate actors invariably remain motivated by profit and market dominance, which may include international stakeholders of significant control. If regulatory constraints become too onerous, or if an alternative jurisdiction offers more permissive conditions, companies may pivot, creating friction with their host or home state.

Multinational ‘alliances’ and compliance: Large technology firms with global footprints often seek to maintain cordial relationships with multiple governments simultaneously, balancing distinct regulatory requirements. In some cases, these companies form alliances with states that promise stable policy environments or substantial investment in AI infrastructure. However, their international reach can also undermine national governance if they exploit cross-border regulatory gaps or shift operations to avoid restrictions on data collection, surveillance technologies, or dual-use AI applications.

Tensions between national security and corporate autonomy: Where antagonist or adversarial dynamics prevail among states, corporations are frequently caught between conflicting regulatory demands. Governments may compel technology firms to withhold products or services from geopolitical rivals, while the same firms grapple with shareholder expectations to maximise profits in those rival markets. Such dilemmas can produce a patchwork of contradictory regulatory obligations, intensifying the challenge of establishing coherent global AI governance.

The competition continuum of AI governance is not solely driven by state actors jockeying for strategic advantage, but also by corporations whose allegiances are subject to complex, sometimes contradictory, market pressures. Whether states and corporations align in cooperative, competitive, or adversarial modes will ultimately determine the shape of emerging norms, standards, and institutions — reshaping the global order.

Cases

Over years and decades, this persistent competition erodes the traditional peace/war dichotomy. We end up in a world where hostile influence is a daily reality. Even nations formally at peace find themselves under near-constant cyber intrusion, intellectual-property theft, economic coercion, or influence operations. A vivid example is the revelation in 2023 that Chinese state-sponsored hackers had infiltrated critical-infrastructure networks in the United States and quietly maintained persistent access. U.S. agencies assessed that these actors were “pre-positioning themselves on IT networks for disruptive or destructive cyber-attacks against U.S. critical infrastructure in the event of a major crisis or conflict.” In other words, an adversary was effectively at war within U.S. networks – mapping targets and planting backdoors – even though no formal state of war existed.3 Similarly, Russia’s long-running campaigns of election interference and cyber-espionage against Western countries, Iran’s cyber- and proxy attacks across the Middle East, and North Korea’s brazen hacks for profit and disruption all illustrate a constant adversarial posture.

Awareness

This environment puts a premium on situational awareness and agility. When competition is persistent and adversarial by default, a nation cannot afford to be complacent during “peacetime,” because peacetime as such doesn’t truly exist in a pure form. Security agencies must be on alert 24/7 across all domains (land, sea, air, space, cyber, information) to detect and counter threats. Strategic surprise becomes a grave risk – if you assume peace until war is declared, you will be fatally behind in responding to the myriad silent attacks that started long before any declaration. Hence, concepts like integrated campaigning and whole-of-government coordination (discussed in the next section) have gained prominence: they recognise that diplomacy, military posture, intelligence, economic tools, and now AI capabilities all need to work in concert continuously, not just mobilise when war “breaks out.” The line between foreign and domestic security also blurs, since adversaries will target internal weaknesses (social divisions, private-sector infrastructure, etc.) even outside of combat.

In summary, the modern security landscape is one of permanent contest. The actors who succeed will be those who can operate effectively in this grey zone – deterring overt aggression while simultaneously competing every day through subtler means. For AI defence, this means our approach to AI can’t be siloed as a tech issue or confined to wartime scenarios; it has to address how AI is used in this ongoing strategic competition, both to enhance our own resilience and to guard against adversaries’ AI-augmented tactics.

Part 1: War is Not How Wars are Waged

Part 2: Persistent Competition and the End of the Peace–War Dichotomy

Part 3: Integrated Campaigning and Cross-Domain Synergy

Part 4: Frontier AI, Control Dilemmas, and the Race for Supremacy

Part 5: Offensive AI, New Weapons, and New Risks in Escalation

Part 6: Defensive AI, Resilient Infrastructure, and Safeguarding Society

Part 7: Conclusion (Navigating an Unseen Battlefield)

Part 8: Appendix — The Human-AI Relationship

Joint Doctrine Note 1-19 (U.S. DoD, 2019)

Competition continuum: replaces the simplistic peace/war dichotomy with three overlapping conditions – cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict – across which states employ all instruments of power simultaneously.

Arguably, this ‘Competition Continuum’ is a neutral term that gets are Clausewitz’s idea of Grand Strategy. Clausewitz would suggest war is just one tool to achieve specific political ends, not all too unlike the notion of conflict being driven more by obtaining strategic objectives than a desire of total conquest. Further, Clausewitz’s position implies the existence of other tools of statecraft that may be used to obtain political ends, namely economic and diplomatic means. I think it’s fair to suggest that the ‘Competition Continuum’ dynamic merely steps slightly further back in order to contextualise politics as just another mode of operation to achieve strategic ends.

Security dilemma: A classic concept in international relations: measures one state takes to enhance its security are interpreted as threats by others, prompting reactive build-ups and potentially spiralling competition. In the grey-zone era, aggressive cyber and AI deployments can provoke precisely this dynamic, as rivals feel compelled to match or pre-empt them.

Volt Typhoon: Codename for a Chinese state-sponsored cyber group that infiltrated U.S. critical-infrastructure networks (telecoms, power grids, especially in Guam) in a stealthy 2023 campaign. Using “living-off-the-land”techniques, the actors pre-positioned themselves for potential sabotage in a future crisis.